Chapter 10.4-10.5

Polar Coordinates

When a parameter t is involved, x and y can be defined separately in terms of t, resulting in a parametric equation. Learn about parametric equation and their roles in calculus.

Chapter 10.4

Polar Coordinates and Polar Graphs

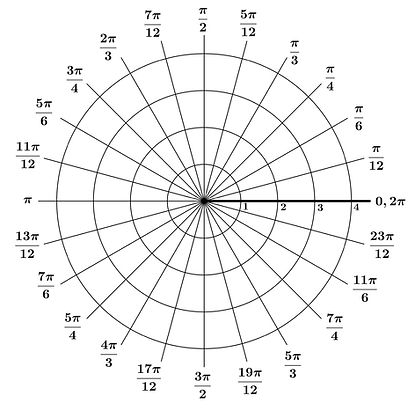

To form the polar coordinate system in the plane, fix a point O, called the pole (or origin), and construct from O an initial ray called the polar axis. Then each point P in the plane can be assigned polar coordinates (r, θ), as follows.

r = directed distance from O to P

θ = directed angle, counterclockwise from polar axis to segment OP

In this system, it is convenient to locate points with respect to a grid of concentric circles intersected by radial lines through the pole.

Theorem 10.10 - Coordinate Conversion:

The polar coordinates (r, θ) of a point are related to the rectangular coordinates (x, y) of the point as follows.

1. x = r cos θ

y = r sin θ

2. tan θ = y / x

r^2 = x^2 + y^2

Theorem 10.11 - Slope in Polar Form:

If f is a differentiable function of θ, then the slope of the tangent line to the graoh of r = f(θ) at the point (r, θ) is

dy/dx = (dy/dθ) / (dx/dθ)

= ( f(θ) cos θ + f′(θ) sin θ ) / ( - f(θ) sin θ + f′(θ) cos θ )

provided that dx/dθ ≠ 0 at (r, θ).

From Theorem 10.11, you can make the following observations.

-

Solutions to dy/dθ = 0 yield horizontal tangents, provided that dx/dθ ≠ 0.

-

Solutions to dx/dθ = 0 yield vertical tangents, provided that dy/dθ ≠ 0.

If dy/dθ and dx/dθ are simultaneously 0, no conclusion can be drawn about tangent lines.

Theorem 10.11 has an important consequence. Suppose the graph of r = f(θ) passes through the pole when θ = α and f′(α) ≠ 0. Then the formula for dx/dy simplifies as follows

dy/dx

= ( f(α) cos α + f′(α) sin α ) / ( - f(α) sin α + f′(α) cos α )

= ( f′(α) sin α + 0 ) / ( f′(α) cos α - 0 )

= sin α / cos α

= tan α

So, the line θ = α is tangent to the graph at the pole, (0, α).

Theorem 10.12 - Tangent Line at the Pole:

If f(α) = 0 and f′(α) ≠ 0, then the line θ = α is tangent at the pole to the graph of r = f(θ).

Special Polar Graphs:

Chapter 10.5

Area and Arc Length in Polar Coordinates

Theorem 10.3 - Area in Polar Coordinates:

If f is continuous and nonnegative on the interval [α, β], 0 < β - α ≤ 2π, then the area of the region bounded by the graph of r = f(θ) between the radial lines θ = α and θ = β is given by

A = 0.5 ∫ (α -> β) [ f(θ) ]^2 dθ

= 0.5 ∫ (α -> β) r^2 dθ

NOTE: You can use the same formula to find the area of a region bounded by the graph of a continuous nonpositive function. However, the formula is not necessarily valid if f takes on both positive and negative values in the interval [α, β].

Theorem 10.14 - Arc Length of a Polar Curve:

Let f be a function whose derivative is continuous on an interval α ≤ θ ≤ β. The length of the graph of r = f(θ) from θ = α to θ = β is

s = ∫ (α -> β) √( [f(θ)]^2 + [f′(θ)]^2 ) dθ

∫ (α -> β) √( r^2 + (dr/dθ)^2 ) dθ

Theorem 10.15 - Area of a Surface of Revolution:

Let f be a function whose derivative is continuous on an interval α ≤ θ ≤ β. The area of the surface of revolution formed by revolving the graph of r = f(θ) from θ = α to θ = β about the indicated line is as follows.

1. S = 2π ∫ (α -> β) f(θ) sin θ √( [f(θ)]^2 + [f′(θ)]^2 ) dθ

(about the polar axis)

2. S = 2π ∫ (α -> β) f(θ) cos θ √( [f(θ)]^2 + [f′(θ)]^2 ) dθ

(about the line θ = π/2